Networks in the Paris art scene reflected in Imre Pán’s activity (2.)

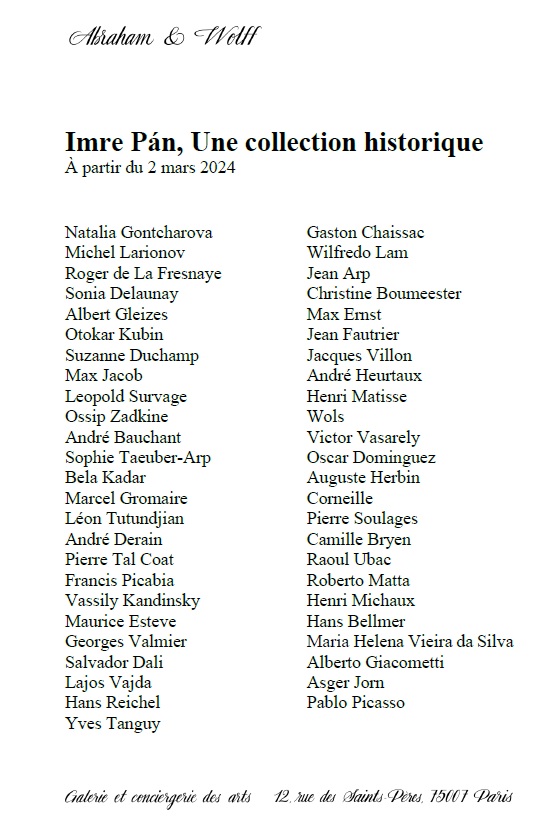

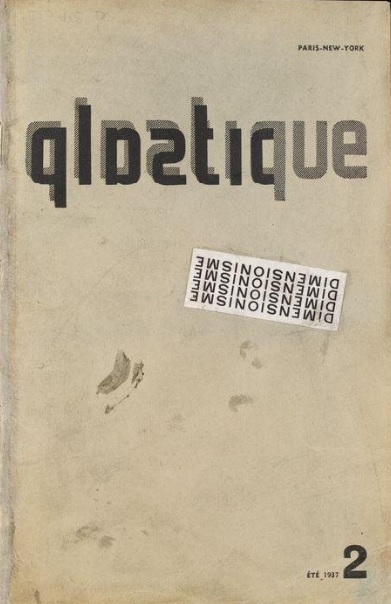

During his Paris years ‒ which means a relatively short period, between 1957 and 1972 ‒, Imre Pán succeeded to develop strategies of artistic activities and ways of circulating ideas that seemed quite singular for the period. There are at least two reliable sources for documenting these activities and their objectives: one of the possibilities is to check the lists of publications on display at Galerie Jocelyn Wolff for any possible patterns on the list of artists that Imre Pán chose to cooperate with. Another possibility is to extend the investigation, and include the works from Imre Pán’s private collection, exhibited at Abraham&Wolff under the title Imre Pán, A historical collection. I argue that some of these choices can be connected to the previous decades of Imre Pán’s activity within the Hungarian art field.

The specificity of Imre Pán’s activity as an art curator and publisher can be seen from different angles. In Marjorie Micucci’s interpretation, written for the Jocelyn Wolff exhibition, one of the possibilities is to see the choices in their aspects related to historical time: what Imre Pán attempted to do was to think outside the box of the trends and fashionable art forms, trying to offer alternative routes for artists: “his choices paradoxically revealed a singularity that took little account of emerging trends and movements”. What he offered was also a very conscious affirmation of plurality: “Plurality was asserted. The collective was asserted. The influence of abstraction and surrealism was reasserted. To look at a work, was to look through the infinite possibility of connections and disconnections, discordances and correspondences.” In short, a synthetic approach was preferred to an exclusivist one. This synthetic nature can be identified as a model in the East Central European avant-gardes in the interwar period, and also, more specifically, in artistic endeavours that Imre Pán was involved with before coming to Paris ‒ namely, in projects such as the magazine IS (1924-1925) co-edited by Pán, or the activity of the European School (1945-1948), with Pán among its founding members.

This synthetic nature does not work along the lines of the ‘anything goes’ principle, however. There are some clear guiding lines ‒ in the case of IS, mainly Dada, constructivism and surrealism. For the European School, surrealism and abstraction. Later on, during the Paris years, we can identify trends like geometric and concrete abstractions, optical abstractions, informal works, in addition to post-surrealist figurative works, many of them connected to the Cobra movement (1948-1951) and its echoes. The nature of the synthesis can therefore be identified more precisely through the functionality of artistic networks. Unraveling these aspects may lead us to a better understanding of Imre Pán’s strategies. In the following paragraphs I will give four examples of artistic contacts that were later on rearticulated in Imre Pán’s editorial and artistic activity in Paris.

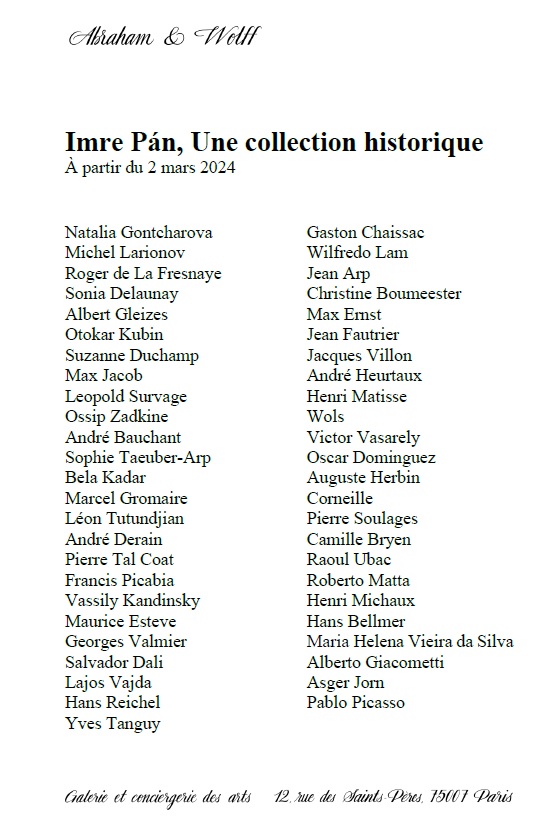

In 1962, Imre Pán published a poem in the 10th issue of KWY, a magazine founded by Lourdes Castro and René Bertholo, and named after the three letters that do not exist in the Portuguese alphabet. The title of the poem, La mémoire de Dada, could have echoed personal experiences of Pán, from his youth. However, the poem is a reconstruction of the reverberations of the international Dada movement, with references to artists like Tristan Tzara, Georges Ribemont-Dessaignes, Francis Picabia, Hans Arp. The poem ends with these lines: “Arp la troisième grâce a taillé des nuages / monuments qui dans le désert humain / donnent de la pluie à la sécheresse de l’âme”, referring to Arp’s post-dada career in a positive light. Pán’s previous contacts with Arp’s works can be traced back to 1924, when in the magazine IS, co-edited by Pán, was published a poem by Arp (Befiederte Steine). This is a first example of renewed interests that connect Imre Pán’s different periods of activity. IS was considered by many a promoter of Dada approaches in Hungarian culture, and we can argue in favour of this opinion in many ways ‒ through the presence of dada negations and performative approaches to the editing process itself, and, in addition, the presence of sound poetry and other disjointed types of experimental texts in the material published by the editors.

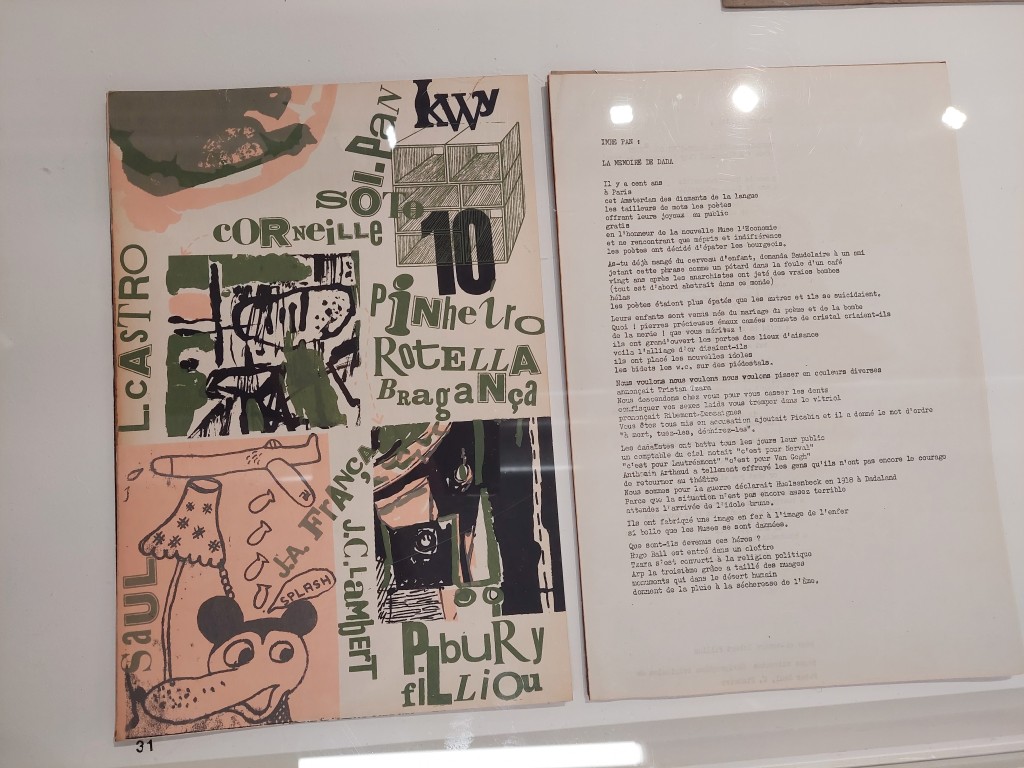

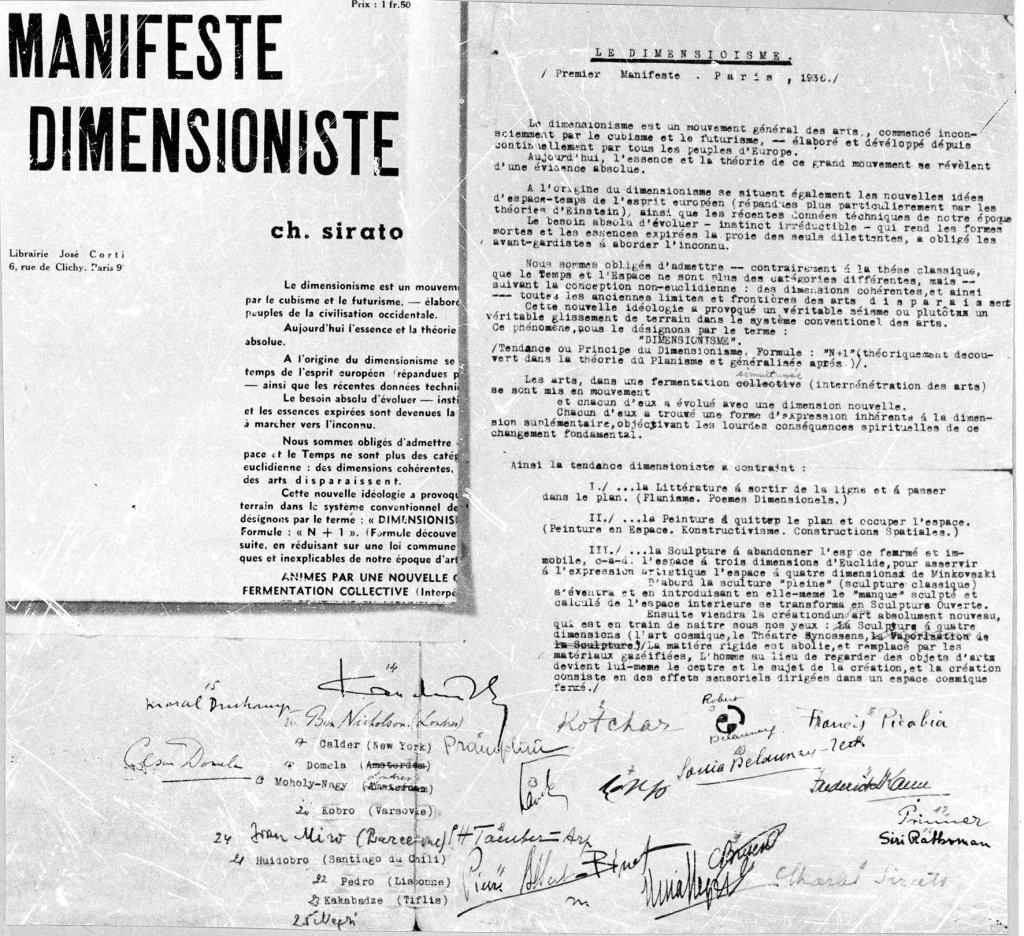

A later stage in Arp’s contacts with Hungarian culture can be identified in the story of the Dimensionist Manifesto (1936), initiated by Hungarian poet Charles Sirato / Tamkó Sirató Károly. Arp was quite enthusiastic about the concept of Dimensionism. After its first publication, Sophie Taeuber-Arp was the second to republish the text of the manifesto in her review Plastique, in 1937.

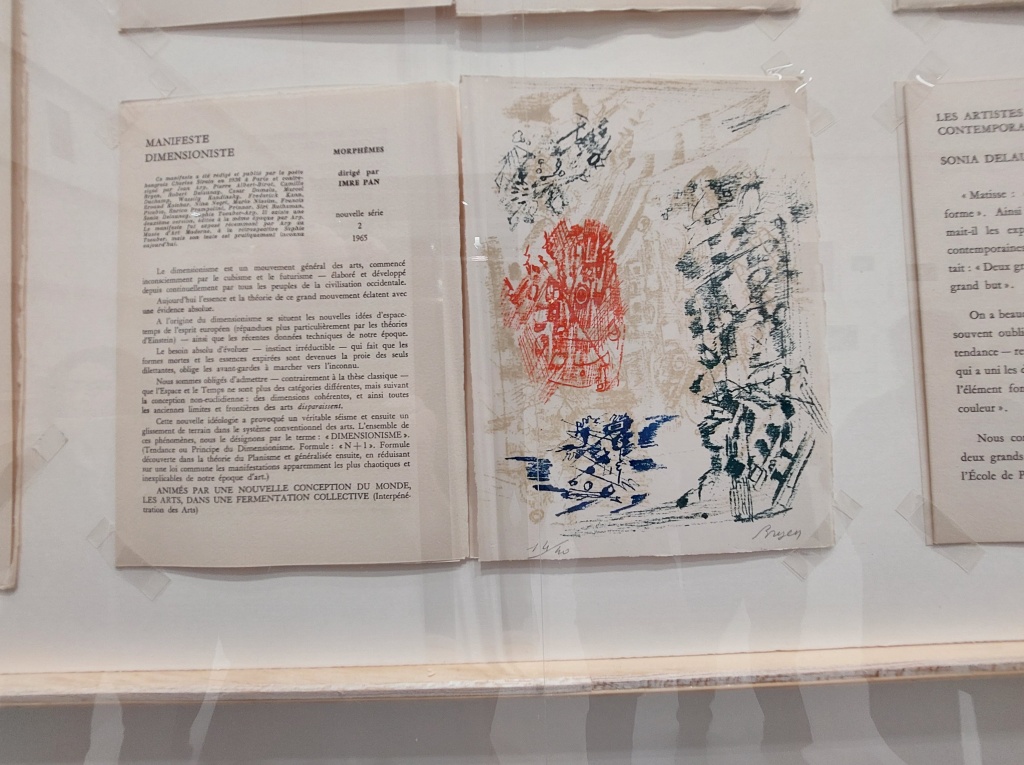

The third publication of the manifesto was in Imre Pán’s collection, in Morphèmes (1965). The story of Dimensionism cannot be summarized in such a brief text, but for our investigations it is important that the brothers Árpád Mezei and Imre Pán were clearly in contact with Tamkó Sirató Károly after his relocation to Hungary in 1936, so they must have known about the story of Dimensionism presumably as early as the 1930s, and even more probably during the 1940s, while they were involved in the European School project, among whose members Sirató was listed. Dimensionism adopted a synthetic view upon the avant-garde, just like the majority of the East Central European avant-garde groups, and just like Imre Pán throughout his own career.

The Dimensionist Manifesto was signed by artists like Hans Arp, Francis Picabia, Vassily Kandinsky, Robert Delaunay, Marcel Duchamp, Camille Bryen, Sonia Delaunay-Terk, Sophie Taeuber-Arp, Ervand Kotchar, Pierre Albert-Birot, among others. The presence of Camille Bryen among the authors of Morphèmes may be connected to this previous Dimensionist episode. Bryen was considered by Sirató as surrealist by the time of the publication of the manifesto, while later on he evolved towards lyrical abstraction and tachisme. So if we look for arguments in favour of the presence of authors like Arp or Bryen in the publications of Pán, we may find these previous episodes relevant.

The Pán collection, exhibited at Abraham&Wolff reconfirms these connections: Imre Pán had in his collection works by Bryen, Sophie and Jean Arp, Sonia Delaunay, Francis Picabia, Vassily Kandinsky. Although these names were quite well-known within avant-garde circles, I argue that the Dimensionist episode may have drawn Pán’s attention towards them to a greater degree, and may have been an additional argument for including them into his private collection.

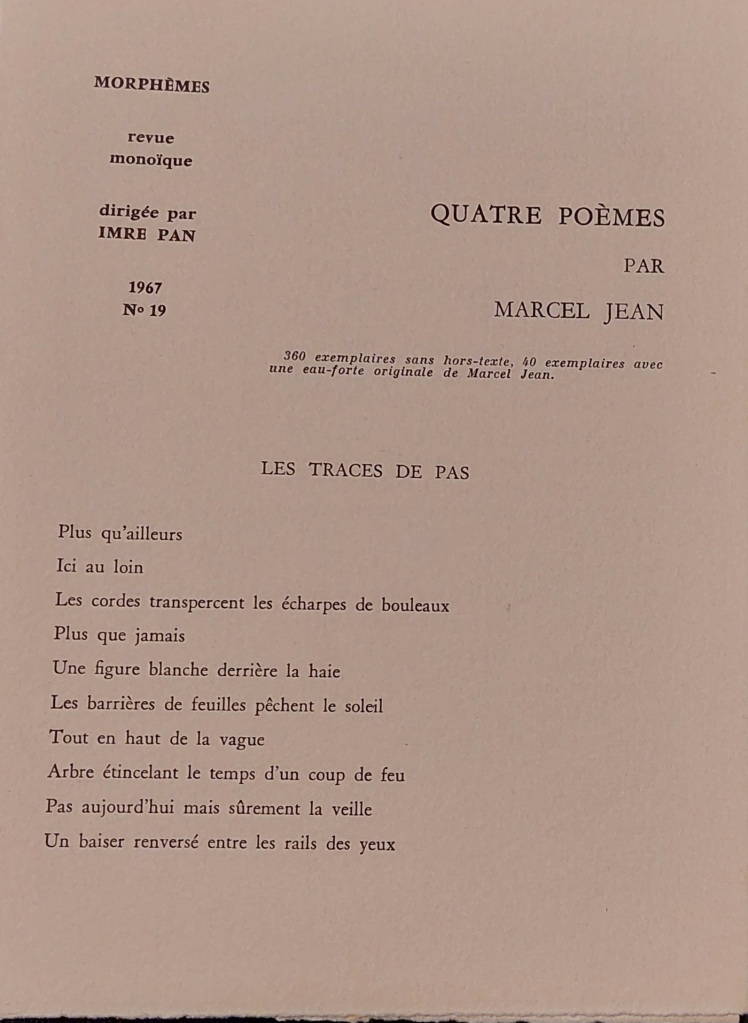

Chronologically, the third connecting element between Pán’s Hungarian period and his Paris activity is his relationship with surrealism. This relationship is mediated by Marcel Jean, member of the Paris surrealist group, who lived in Budapest between 1938 and 1945. Marcel Jean himself is present in Pán’s publications, in Signes and Morphèmes. In my monograph about Hungarian surrealism, I argued that for the second wave of Hungarian surrealism, incorporated into activities within the European School, the presence of Marcel Jean in Budapest was inspiring and essential.

In Imre Pán’s collection of artworks, currently exhibited at Abraham&Wolff, surrealism is represented quite strongly. Works by Salvador Dalí, Yves Tanguy, Wilfredo Lam, Max Ernst, Oscar Dominguez, Roberto Matta, Hans Bellmer, Alberto Giacometti, Raoul Ubac prove that the orientation of the European School towards postwar surrealism was no accident. Imre Pán remained attached to the values of surrealism also during the next few decades.

One last connecting element between Imre Pán’s Hungarian and Paris periods is Cobra. Jacques Doucet and Corneille (Corneille Guillaume Beverloo), future founders of the Cobra group, both visited Hungary during 1947. Their exhibitions in Budapest were organized by Imre Pán. The strong presence of Cobra artists (among them, Corneille, Jacques Doucet, Asger Jorn and Christine Boumeester) in Imre Pán’s publications can convincingly be connected to these previous contacts.

To conclude, we can highlight once more the synthetic and networked character of Imre Pán’s activity, in connection with his Budapest period. The current Paris exhibitions show in detail how, based on previous contacts, Imre Pán was able to incorporate further dimensions to his previous concept about the avant-garde. His newly introduced artists were inclined towards abstraction and neo-dadaist influences, but Imre Pán managed to create for them an institutional background that was acceptable for artists representing the new generations, and who were open to experimenting with techniques of surrealism and abstraction as well.

(Imre Pán, a European Artistic and Publishing History in Paris in The 1960s – Galerie Jocelyn Wolff, Romainville, March 3 – April 20, 2024, Curator Marjorie Micucci)

(Imre Pán, A historical collection – Galerie Abraham&Wolff, Paris)

Balázs Imre József