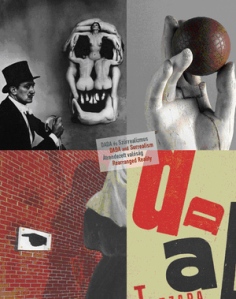

(Hungarian National Gallery, 9 July – 5 October 2014)

Only a tiny number of books by André Breton have been translated into Hungarian so far (Nadja, Poisson soluble, Les champs magnétiques), and they had no real impact on Hungarian culture. Ironically, this fact can be proved also by the generous catalogue of the most important Surrealist overview to date in this country: Dada and Surrealism / Rearranged Reality. In the Hungarian text of the catalogue, Les champs magnétiques is translated as Mágneses terek several times, while the existing translation of the volume was published as A mágneses mezők. Breton is not a recurrent point of reference in Hungarian culture, although painters like Salvador Dalí, Max Ernst or René Magritte – major presences also in this catalogue — are of course well-known by the Hungarian public.

While the reception of Surrealism in Hungary still lacks precision and information, the representative exhibition of the National Gallery, organized in partnership with The Israel Museum of Jerusalem is a very important step in this direction, precisely because of its “introductory” character, that is to be felt in the selection of the exhibited works (in several cases no more than 2-3, but quite representative works by artists like, most importantly, Marcel Duchamp and Man Ray, also Joan Miró, Max Ernst, Salvador Dalí, René Magritte, Hans Arp, André Masson, Roberto Matta, Victor Brauner, Wilfredo Lam, and with the participation of Giorgio de Chirico, Paul Delvaux, Leonora Carrington, Dorothea Tanning, Marcel Jean and others), but also in the keywords that are used for the arrangement of the exhibition.

The keywords are selected also in a way that they stress upon the continuity of the Dada and Surrealist projects: Marvelous Juxtapositions: Collage, Assemblage, Object; Automatism, Biomorphism and Metamorphosis; Illusion and Dreamscape; Desire: Muse and Abused – these are the titles that helped the curators arrange the artworks. Dada in its strict sense is represented here by collages, assemblages and ready-mades by artists like Kurt Schwitters, Marcel Janco, Francis Picabia, Hannah Höch, and by those who themselves mark the transition from Dada to Surrealism: Duchamp, Man Ray, Max Ernst. The most important result of this selection is that Dada is presented here via Surrealism, seen from a backward glance, but another result is that the role of objects, photographs and collages have a greater importance for Surrealism within this exhibition than it was presumed for quite a long time. This way, although this aspect is not highlighted very much, the “introductory” character of the exhibition may refer also to the more recent turns within the interpretations of Surrealism, centered now more and more upon the Surrealist objects and Surrealist photos.

This interpretative framework is present mostly in Dawn Ades’s text (From Dada Collage to the Surrealist Object) in the catalogue, who shows very clearly the points of transition from Dada to Surrealism. Werner Spies’s article in the catalogue (From Dada to Surrealism: The Power of Image Collision to Create Beauty), adapted from a fragment of his 2002 book Surrealismus 1919-1944: Die surrealistische Revolution, is more traditional in its approach based on Surrealist painting, but among the painting techniques he also stresses the importance of the technique of collage and of “pasted papers”.

An important issue is discussed by Adina Kamien-Kazhdan, related to the psychological sources behind Surrealism in the article Automatism and Rorschach: Probing the Unconscious. The author claims to refer to a source “as yet unexamined, looking at the processes involved in Surrealist automatism in relation to Rorschach’s inkblot test.” The context of the research is well documented, the possible links between Surrealist thought and the Rorschach method are presented in a convincing way, but some aspects would need further investigations. The first reference of a Surrealist to the Rorschach test is identified here to be Ithell Colquhoun’s essay The Mantic Stain, from 1949, that erroneously calls the test “The Roschauer method”. Kamien-Kazhdan also speculates upon the fact that Marcel Jean mentions the Rorschach test several times, in different works, coming to the conclusion that “the abundance of information concerning Rorschach’s ideas and test suggest Jean was a Rorschach scholar.” In fact, these references are indebted to the expertise of Jean’s co-author and friend Mezei Árpád in this field, who published already in this early period a scholarly article about this issue (La théorie du psychodiagnostic de Rorschach, Revue de Morpho-Physiologie Humaine, Paris, no. 1, Octobre 1948) earlier than Colquhoun’s reference, and familiarized Jean with this method during Jean’s stay in Budapest, between 1938-1945. Although most of the text of The History of Surrealist Painting was written by Jean, his book of memories confirms that the structure, the theoretical ideas and psychological background of the work was based on Mezei’s notes. Although this piece of information is not central to the thesis of the author, and her contribution to the history of Surrealism is quite relevant, linking this aspect of the Rorschach method to the Budapest exhibition and to Hungarian culture is a missed opportunity of the article.

The presence of the material coming from The Israel Museum was a great opportunity for the curators to promote Hungarian Dada and Surrealist art for a much larger audience than before. The twin exhibition of Dada and Surrealism, called Rearranged Reality: Creative Strategies in Hungarian Art under the Spell of Dada and Surrealism was however received in a more ambivalent manner than the material coming from Jerusalem mainly because of the lack of a coherent vision and narrative. While Dada and Surrealism was curated by Adina Kamien-Kazhdan, the Hungarian material is presented by four curators: Gergely Mariann, Kolozsváry Marianna, Kumin Mónika and Százados László. Even though their visions are able to create interesting connections between the Hungarian and the international material, the logic of these connections is quite different from room to room, and seems much more subjective and disputable than the more established structuring of the international artworks.

Hungarian Dada is presented mainly in connection with Kassák Lajos and his journals and books edited in Vienna, while the presentation of Hungarian Surrealism based on the activity of the European School (Bálint Endre, Korniss Dezső, Anna Margit, Bán Béla, Rozsda Endre, Lossonczy Tamás and others), but reaching beyond the period of the School, presenting also Ország Lili, Gedő Ilka and an unexpected number of collages by Bálint, Ország, Jakovits József, but also Reigl Judit and Vajda Lajos. Acknowledging the fact that in Hungary there was no proper Dada or Surrealist group activity, the exhibition presents the irradiation of these currents to different periods and different artistic fields. Besides the large number of collage and assemblage pieces it is astonishing to see the image of Gyarmathy Tihamér’s flat from the 1980s, a genuine Surrealist location and at the same time an interesting replica of André Breton’s studio that can nowadays be seen in an approximative reconstruction at the Centre Pompidou in Paris.

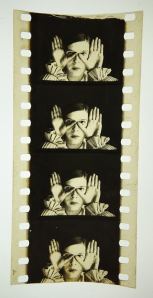

A successful and insightful subplot of the Hungarian and international avant-garde can be explored in the same building of the National Gallery: (Film) Experiments Brought to Life. The First Cinema of the Avant-Garde. (Curator: Orosz Márton) Here a greater influence of popular genres can be felt: animations, comic strips, toy designs constitute an important context for Dada and Surrealist visuality. International authors like Man Ray, Fernand Léger, Viking Eggeling, Hans Richter, Luis Bunuel and Salvador Dalí are present with their movies or movie fragments, but the most interesting novelties of the exhibition are Bortnyik Sándor’s animation (Mr. Pipe rettenetes éjszakája) and a reconstruction of Gerő György’s movie Béla (1926), recreated by Bruce Checefsky based on Gerő’s notes, screenplays and published shots of the movie.

Through the figure of Gerő, the presence of Dada in Hungary is reconstructed also through its other dimensions, the review co-edited by Gerő, called IS getting a greater attention within this exhibition than in Rearranged Reality downstairs. IS is important because through its co-editors and authors Pán Imre and Mezei Árpád the Hungarian Dada and Hungarian Surrealism can be presented also in a sort of continuity, at least as far as the personal networks are concerned. Although Pán or Mezei cannot be described as Dada authors (if they are anything, then they are Surrealists), IS publishes Dada literature by Kristóf Károly or Gerő György, and later, Mezei and Pán will be the most important promoters of Surrealism through the European School and its publications.

Most interesting among the Hungarian texts of the catalogue is Hornyik Sándor’s The Spirit of Montage: The “Surrealist” Mineshafts of Hungarian Visual Arts, which goes beyond presenting an issue and succeeds in problematizing it. It is an essay rather than an academic article, but if we read this text together with another text by Hornyik, related to the very same exhibition (Az anyag misztériuma: A szürrealizmus és a modernitás újraértékelése a 20. század végén, Új Művészet, July 2014), we will see that with these two texts, the spirit of Surrealism indeed entered the Hungarian cultural field, and we might even conclude that according to Hornyik’s vision the international material itself might acquire new accents and proportions. Hopefully this is not the last opportunity to see such an exhibition.

Balázs Imre József

Dada and Surrealism. Magritte, Duchamp, Man Ray, Miró, Dalí

Selected works from the collection of the Israel Museum, Jerusalem

Curator: Dr. Adina Kamien-Kazhdan (The Israel Museum, Jerusalem)

Rearranged Reality

Creative Strategies in Hungarian Art under the Spell of Dada and Surrealism

Curators: Mariann Gergely, Marianna Kolozsváry, Mónika Kumin, László Százados (Museum of Fine Arts – Hungarian National Gallery)

(Film) Experiments Brought to Life. The First Cinema of the Avant-Garde

Curator: Márton Orosz (Museum of Fine Arts – Hungarian National Gallery)